If you were a kid growing up in the U.S. during the ’80s and ’90s, entertainment had a certain shape. It was full of suburban lawns, the excitement of excess, gated communities, and nostalgia for the soda-fountained, saddle-shoed “simplicity” of post-WWII values. Flashy blockbusters were the rule of the day. In the face of reasserted homogeny, a specific set of subcultures flourished, grown out of punk movements and other anti-establishment groups. Which is a roundabout way of saying, if the mainstream didn’t float your boat (or only did part of the time), chances are, you were a Tim Burton kid.

Burton sidestepped his way into cinema juggernaut status, getting his start in Disney’s animation division before being fired and sweeping into feature films. He quickly made a name for himself by being “too dark” and “too creepy” for children (plenty of actual children who grew up on his films would dispute this claim), and for a distinct visual vernacular born of gothic sensibilities intertwined with a deep understanding of old monster movies, low-budget sci-fi films, and German Expressionism. But there is something even more fascinating about Tim Burton films, especially when looking back on the director’s career: They often seem to center male protagonists when they are plainly about women.

This is isn’t true for every single Tim Burton film, of course—there are quite a few of them at this point—and it’s also probable that Burton himself didn’t always realize this common anchor in his own projects. But with the exception of the films he adapted from stories and biographies focused on men and boys (Ed Wood, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Big Fish, and so on), most of Burton’s works showcase female protagonists who initially appear to be secondary characters, and eventually pull the focus of the plot toward themselves. In effect, Burton’s heroes (many of them admittedly modeled after himself in some fashion) are a gender-flipped version of the “manic pixie dream girl” trope—they are men who bring magic, strangeness, and wonder in the lives of his female protagonists, and then either vanish or reorder their own worlds around said female protagonists. Burton’s “nervous gothic dream boys” facilitated female-centered narratives at a point in time when those narratives were (and still often are) hard to come by.

Among the first feature films that Burton directed were Beetlejuice and Edward Scissorhands. Set in the idyllic countryside and a nameless pastel suburbia (respectively), both of these films are titled after their male protagonists: Beetlejuice, the “bio-exorcist” ghost who torments the Deetzes and Maitlands once he’s unleashed in their Connecticut home, and Edward, created by an inventor who failed to complete his “son” before he gave him hands, leaving him with sets of scissors instead. From their titles alone, one would assume the films are about the male characters, and the performances by Michael Keaton and Johnny Depp seem to back this up. Beetlejuice is a scene-stealer in his brief 17-minutes of screen time, and Edward is a picture of soft naiveté dressed in fetish gear. Still, if we’re paying attention, the story of each film is truly about their young female hero—Lydia Deetz and Kim Boggs—both, in this particular instance, played by Winona Ryder.

Following the death of the Maitlands and their journey to ghosthood, everything that occurs in Beetlejuice revolves around Lydia; she is the one who reads The Handbook of the Recently Deceased and learns to see Adam and Barbara, she’s the reason that Maitlands stop trying to evict the Deetzes from their house, she’s the one who calls Beetlejuice back once he’s been banished in order to save her friends, she’s the one Beetlejuice tries to marry. Beetlejuice may be a perverted chaos demon making constant gags throughout to keep things lively, but this is a tale about Lydia Deetz gaining the family she’s always wanted and an environment where her “strangeness” feels right at home. She is the person who the story rewards because she is the one who deserves to be rewarded in the fashion of all protagonists.

Then there’s Kim Boggs, who begins Edward Scissorhands as the girl next door in her perfect nuclear family somewhere in suburban Florida. She’s blond, she’s dating a popular jock named Jim, she has a water bed (back when those were a thing). She’s terrified of Edward on meeting him, but that changes over time, developing into real feelings for him. When Jim can’t handle the thought of losing her to the likes of him, he tries to kill Edward, but ends up dead at his bladed hands. Again, the whole story revolves around Kim—she is the one who changes the most over the course of the story, she is the one who comes to see her home and her town differently, she is the one who protects Edward by telling the community that he and Jim killed each other.

Kim is also the person telling the story; the bracketing device of the narrative is a much older Kim telling her granddaughter why their strange Florida town gets snow in the winter. Edward, as a character, doesn’t truly change. He remains in stasis, unaging, frozen much like the ice sculptures he carves. What he does over the course of the story changes Kim’s life, while he is sent back up to his Gothic castle on the hill with only the memory of people for company. And because Kim is the narrator, the audience can never be sure if she’s altering the story for our benefit and her granddaughter’s.

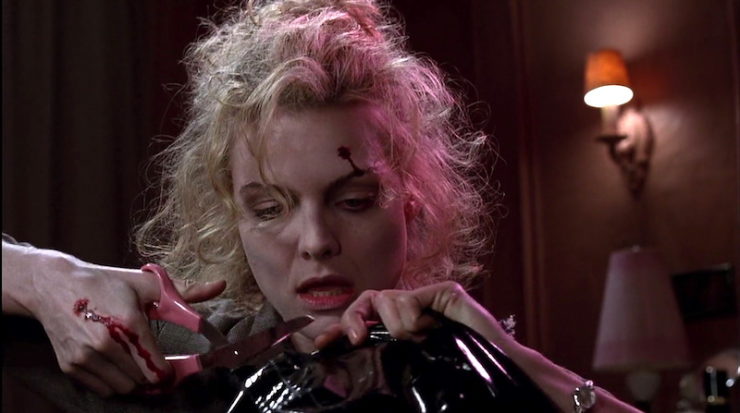

Don’t forget Batman. Burton’s first big budget flick turned out to be a major hit, giving the director the clout he needed to ask the studio for more control over the sequel. And where did that lead? As he commissioned various rewrites of the script, the sequel became a movie about Catwoman. Sure, Batman’s in there somewhere and so is the Penguin, but Batman Returns is a story commanded by Selena Kyle. She’s easily the most captivating character of the film, with more interesting motivations than Bruce Wayne and his alter bat-ego are ever allotted. Batman knows it, too, being so impressed with Selena that he straight up unmasks in front of her before the film comes to the end.

The Nightmare Before Christmas (all based off of a poem Burton wrote that parodied The Night Before Christmas) is meant to be the tale of Jack Skellington’s midlife crisis, but is at least equally about Sally asserting her independence and freeing herself from Dr. Finklestein. Moreover, Sally’s the only person with a lick of common sense in the whole story—at the end, Santa Claus goes so far as to tell Jack that the next time he gets funny ideas about appropriating holidays, “I’d listen to her! She’s the only one who makes sense around this insane asylum…” In reality, it’s a story about Jack Skellington realizing that his life is pretty great, and he’d be a lot better off if he just realized that Sally is perfect.

Following Ed Wood (a stylized biopic) and Mars Attacks! (an ensemble film), Burton did Sleepy Hollow, which centered on Ichabod Crane. In a twist from the original story, Crane is a constable from New York City, sent to investigate murders in Sleepy Hollow as a form of punishment for his insistence on using his own manner of forensics to solve crimes. But—surprise—the murders at Sleepy Hollow unveil a plot surrounding Katrina Van Tassel and her stepmother, Lady Mary Van Tassel. Both of them are witches, though Katrina is the kind sort, unaware that her stepmother is using dark magic to get revenge on behalf of her own family. The entire final act sees Mary kidnap and reveal her scheme to Katrina, not Ichabod, as the constable is barely registers to her at all. By the end of the film, Ichabod brings Katrina and Young Masbeth to New York City with him, away from the horrors of their small town. His entire life is changed by the work he does in Sleepy Hollow, but mainly by Katrina herself. Crane is perhaps the most distilled evolution of the “nervous gothic dream boy” type, mild and odd and arriving precisely when the heroine has need of him. From the moment they set eyes on each other, his world revolves around her.

By the time Burton reached the twenty-first century, he became a bit more overt about the formula—Corpse Bride has a similar outline to many of his early films, but is titled after the true central character instead of “Victor’s Wedding,” or some nonsense. Alice in Wonderland is titled after the book it’s based on, but Burton goes further, making Alice an action hero in full knight’s armor. Dark Shadows, while showing trailers that centered on Johnny Depp’s portrayal of Barnabas Collins (likely a studio decision), focused almost entirely on the women of the Collins family and the revenge sought out by Angelique Bouchard against Barnabas and his descendants. While Burton has tried different types of projects and adaptations, this formula shows up again and again; an odd man surrounded by or beholden to singular, often powerful women.

That doesn’t mean that Tim Burton’s track record goes unmarked, or that he’s better than others at telling women’s stories. In fact, for a person who has made a career telling the tales of “outsiders,” his own library is relatively homogeneous. The director came under fire in 2016 for his response to the fact that his casts are overwhelmingly white, where he responded vaguely that “Things either call for things or they don’t” before going on to explain that he wouldn’t say that Blaxploitation films needed more white people in them. His milieu is rife with empty spaces that his stories never bother to fill in—all the female characters that he showcases are white, straight and cisgender, and otherworldly in one sense or another. Many of them were modeled after Burton’s own muses at the given time; Sally was famously modeled after partner Lisa Marie, and Helena Bonham Carter was clearly a template in his later work. There’s very little variation, and that appears to be purposeful on the director’s part overall.

But Burton’s movies still made room for narratives that popular entertainment often wasn’t looking to sell—allowing women to simply take up space and be relevant. Even if they were angry, even if they were frightened, even if they were weirdos. Even if their fairy tales ended in death, or something far stranger. They were not superfluous prizes for men to attain, but women doing what women often do—incalculable and often unseen labor, constantly working on behalf of others emotionally and physically (sometimes to their own detriment). Whether it was Lydia calling on a monster to save her adoptive ghost parents, Sally trying to reason Jack out of taking over Christmas, Emily letting go of Victor so Victoria can have the happiness she never had, Alice saving Wonderland and her father’s company all at once, Selena trying to expose Max Shreck’s horrific business practices, Katrina doing magic to keep others from harm, Kim protecting Edward from an angry mob, or Elizabeth Collins Stoddard doing everything in her power to defend her family, they are all resourceful women of action in stories where awkward goth men are at a loss for what to do. And acknowledging that work at all often feels radical in a world where we still don’t seem to quantify women’s contributions.

It has always been a welcome diversion from the usual formulas. And despite its flaws, Tim Burton’s canon will always be a little extra subversive for it. While it’s easy (and fun) to joke about the director’s over-pale leading men, the people who they share the screen with are the ones who really deserve the attention. It may be time to reconfigure how we think of Burton’s films, and what they offered to many odd kids the world over.

Emmet Asher-Perrin will also always be thankful to Tim Burton for Danny Elfman soundtracks. You can bug him on Twitter, and read more of her work here and elsewhere.

I don’t think that empty spaces is fair, considering you talk about the great roles and his depiction of them. Is a movie really missing something because it’s not this much diverse? Why should his art have to conform after you praise him for being non-conforming?

@Zen, I believe that if anything being overwhelmingly white makes his works more conformist than the opposite. So much of Hollywood and media has been dominated by white actors for so long that diversity would still only add to his non-conformity in those spaces.

In the (mostly latter) portion of the article, the writer speaks of Tim Burton in past tense; as if he was dead or had lost his creative powers. He’s neither dead nor beyond moviemaking.

Why? That seems like minimizing or denigrating his vision and achievements. If that’s true. say that’s what you think. Don’t use others to say it for you.

Anyone who names a piano brand “Harryhausen” will always have my attention.

Although I would love to see Burton’s take on The Addams Family universe.

I grew up with most of these movies, and I always wondered if it somehow influenced my personality just a bit. Or maybe my personality was what drew me to those movies :) His work might not be able to speak to every demographic but it was definitely something thats spoke to me, although I’m glad in general we have many more options.